GDF11 restores the impaired function of EPCs-MA by promoting autophagy: GDF11 ameliorates endothelial progenitor cell aging by promoting autophagy

doi: 10.1515/fzm-2024-0021

-

Abstract:

Objective Our study aimed to assess the effects of Growth and differentiation factor 11 (GDF11) on the function of endothelial progenitor cells in middle-age individuals (EPCs-MA) isolated from mouse bone marrow and to explore the mechanistic relationship between GDF11 and age-related ALP impairment. Methods Bone marrow-derived EPCs were isolated, culture and GDF11 treatment. In vivo, the mice model of myocardial ischemia (MI) was induced by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and mice were randomly divided into MI group and EPCs transplantation group (EPCs-Y, EPCs-MA, EPCs-MA/GDF11). The positive effect of GDF11 treatment of EPCs-MA on MI was verified by echocardiography and the average ratio of fibrotic area to left ventricular (LV) area. In vitro, the effect of GDF11 on ameliorating EPCs aging by promoting autophagy was confirmed by transwell assay, immunofluorescence staining, characterization of EPCs ultrastructure through transmission electron microscope (TEM), lysosome imaging and Western blot. Result Our findings demonstrate that GDF11 enhances the migration capacity of EPCs-MA and improves recovery of impaired cardiac function after myocardial infarction (MI) in mice, with EPCs isolated from young mice (EPCs-Y) as controls. Moreover, GDF11 restored functional phenotypes of EPCs-MA to levels akin to EPCs-Y, promoting the expression of CD31, endogenous NO synthase, and the restoration of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and CDH5 expression patterns, as well as the formation of Weibel-Palade bodies—key organelles for storage and secretion in endothelial cells and EPCs. Furthermore, GDF11 significantly enhanced the autophagic clearance capability of EPCs-MA by promoting ALP. Conclusions Our results suggest that GDF11 ameliorates cardiac function impairment by restoring the activities of EPCs from aging mice through enhanced ALP. These findings suggest that GDF11 may hold therapeutic potential for improving aging-related conditions associated with declined autophagy. -

Key words:

- GDF11 /

- endothelial progenitor cells /

- autophagy lysosome pathway /

- aging

-

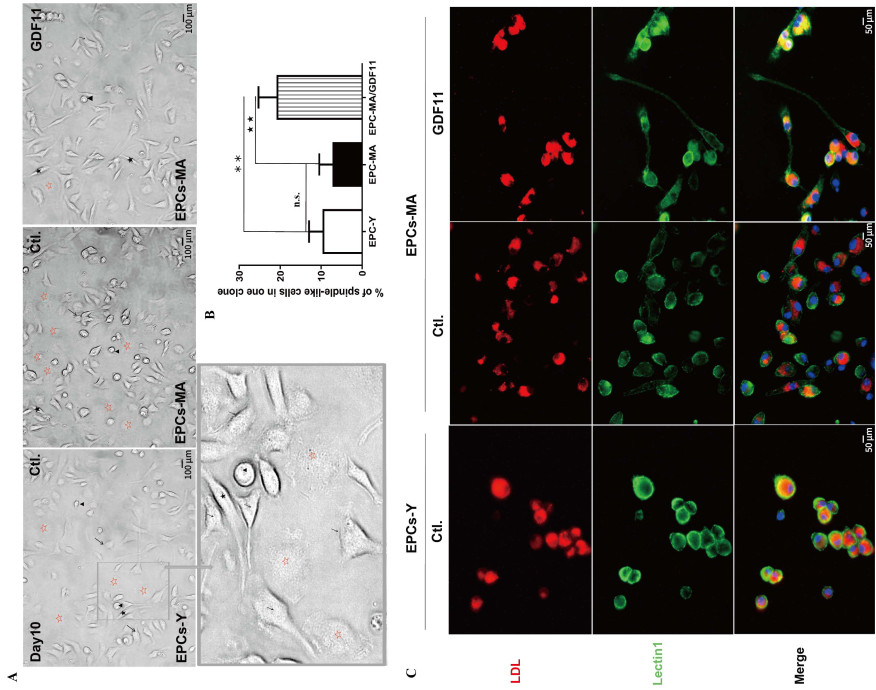

Figure 1. GDF11 changes the ratio of different subpopulations of EPCs-MA based on morphological features

(A) Light microscopic photographs showing mononuclear cells (MNCs) at day 10 in the culture with clusters of cells surrounded by spindle-like cells. Four morphologic subtypes were identified: cobblestone-like cells, spindle-like cells, drop like cells, and flatten round cells, which are marked with arrows, dark stars, arrowheads, and hollowed red stars, respectively. (B) Bar chart showing the percentage of spindle-like cells relative to other subtypes of EPCs. Statistical data on the ratio of spindlelike cell subpopulation are expressed as the mean values of percent spindle-like cells over total number of EPCs per EPCs clones (n = 2 batches in each group). (C) Representative fluorescence images with red staining depicting cells engaging in active Dil-Ac-LDL uptake from the culture medium and green staining for EPCs with lectin UEA-1 (lectin1) binding. The spindle-like cell is marked with black stars; Scale bar: (A) 100 µm and (C) 50 µm; **P < 0.01, ★★ P < 0.01.

Figure 2. Effects of GDF11 on EPCs-MA maturation

Immunofluorescence staining showing the expression and distribution of CDH5 (green) and CD31 (green) primarily in the plasma membrane. (A) CDH5 expressed in EPCs at varying levels and can be classified into low (red arrow), medium (yellow arrow), and high (white arrow) level based on the fluorescence intensity. The majority of EPCs expressed CD31 (yellow arrow), CD31 was negative in few cells (red arrows). (B) Bar chart showing percent cells expressing CDH5 at low, medium, and high levels. (C) Bar chart showing the percentage of CD31 positive and negative cells. Scale bar: 100 µm; **P < 0.01, ★ P < 0.05, ★★ P < 0.01.

Figure 3. Effects of GDF11 on EPCs-MA migration in vitro and in vivo

(A) The experiment procedures for migration assays of EPCs: Prior to EPCs collection, the cells at day 8 in culture were treated with GDF11 for 48 h. The EPCs at day 10 were used for migration assays in vitro and in vivo. For migration assays in vivo, 8-10-weeks-old mice were subject to MI surgery and injection of EPCs via tail vein onehour post-MI. After 14 days, Doppler ultrasonography and histological assays were performed to evaluate cardiac function and measure the infarct size. Statistical data were obtained from 3 independent experiments (n = 3-4 per group). (B) The effect of GDF11 on the migration of EPCs-MA: Migrated cells were visualized after crystal violet staining in blue color. The bar chart present the percentages of migrated cell areas (n = 3 batches per group). Scale bar: 500 µm. (C) Echocardiographic assays depicting the changes of ejection fractions (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) of left ventricle (LV). Cardiac functional parameters of the MI mice and EPCs-Ytransplanted mice were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. n = 5-7/group. (D and E) The hearts were diseected into 3-4 parts from apex to base (D), and peri-infarct tissues (squared) were sectioned and stained with Masson trichrome for assessing infarct size. Fibrotic tissues were stained blue, and the viable tissues were stained red. Collagen (CoL) deposition was quantified with an automated image analyzer, and the data are expressed as percentage of tissue areas. The bar graphs show infarcts size in different groups. Scale bar sizes in Masson section: 2000 µm (E); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ★ P < 0.05.

Figure 4. GDF11 restores the lost functional phenotypes of EPCs-MA

(A and C) Typical examples of immunofluorescence staining images depicting the expression and subcellular distribution of eNOS (red) and vWF (red). eNOS was primarily expressed in the nuclear. In most of EPCs-MA, vWF exhibited a diffuse cytoplasmic signal. vWF was expressed in EPCs at different levels, allowing for classifications into low, medium, and high levels based on the fluorescence intensities. The majority of EPCs expressed vWF at a medium level (yellow arrow), and only small numbers of cells expressed vWF at high (white arrow) and low levels (green arrow), respectively. (B and D) Bar chart showing the percentage of positive area of eNOS expression and cells expressing vWF at low, medium, and high levels, respectively. (E) Photographs captured with TEM showing EPCs with elongated WPBs (arrows) and trans-Golgi networks (TGN) containing enlarged parts where WPBs are formed (arrows heads). (F) Bar chart presenting the mean numbers of WPCs per EPCs, a pile of TNG was recorded as 1 WPB; Scale bar: (A and C) 50 µm; E, 0.5 µm; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ★ P < 0.05, ★★ P < 0.01.

Figure 5. GDF11 enhances autophagic clearance capability of EPCs-MA

(A) The effects of GDF11 on the conversion of endogenous LC3-Ⅰ to LC3-Ⅱ and p62 accumulation, as evidenced by by Western blot analysis. (B) Bar chart summarizing the ratio of LC3-Ⅰ/LC3-Ⅱ and relative protein levels of p62. GAPDH served as an internal control. (C) Autophagic vacuoles were counted under an electron microscope at 10, 000× magnification. All autophagic vacuoles present in each photograph of EPC were counted. Scale bar: 1 µm and 200 nm. (D) Bar chart showing the number of autophagic vacuoles in each EPCs (n = 3). (E) Representative images of LysoTracker Red staining depicting the effects of GDF11 on the lysosomal acidification in EPCs. (F) Bar chart summarizing the percentage of positive areas (accumulated acidic organelles) in EPCs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

-

[1] Loffredo F S, Steinhauser M L, Jay S M, et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell, 2013; 153: 828-839. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.015 [2] Rochette L, Zeller M, Cottin Y, et al. Growth and differentiation factor 11 (GDF11): Functions in the regulation of erythropoiesis and cardiac regeneration. Pharmacol The, 2015; 156: 26-33. [3] Katsimpardi L, Litterman N K, Schein P A, et al. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science, 2014; 344: 630-634. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141 [4] Castellano J M, Kirby E D, Wyss-Coray T. Blood-borne revitalization of the aged brain. JAMA Neurol, 2015; 72: 1191-1194. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1616 [5] Mendelsohn A R, Larrick J W. Systemic factors mediate reversible age-associated brain dysfunction. Rejuvenation Res, 2014; 17 : 525-528. doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1643 [6] Olson K A, Beatty A L, Heidecker B, et al. Association of growth differentiation factor 11/8, putative anti-ageing factor, with cardiovascular outcomes and overall mortality in humans: analysis of the Heart and Soul and HUNT3 cohorts. Eur Heart J, 2015; 36: 3426-3434. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv385 [7] Finkenzeller G, Stark G B, Strassburg S. Growth differentiation factor 11 supports migration and sprouting of endothelial progenitor cells. J Surg Res, 2015; 198: 50-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.05.001 [8] Zhang J, Li Y, Li H, et al. GDF11 improves angiogenic function of EPCs in diabetic limb ischemia. Diabetes, 2018; 67: 2084-2095. doi: 10.2337/db17-1583 [9] Guo Q D, Shao Z B, Wu J, et al. Targeted myocardial delivery of GDF11 gene rejuvenates the aged mouse heart and enhances myocardial regeneration after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol, 2017; 112: 7. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0593-y [10] Hill J M, Zalos G, Halcox J P, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med, 2003; 348: 593-600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022287 [11] Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science, 1997; 275: 964-967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964 [12] Thum T, Hoeber S, Froese S, et al. Age-dependent impairment of endothelial progenitor cells is corrected by growth-hormone-mediated increase of insulin-like growth-factor-1. Circ Res, 2007; 100: 434-443. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257912.78915.af [13] Rigato M, Avogaro A, Fadini G P. Levels of circulating progenitor cells, cardiovascular outcomes and death: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Circ Res, 2016; 118: 1930-1939. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308366 [14] Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo A M, et al. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature, 2008; 451: 1069-1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639 [15] Nakamura S, Yoshimori T. New insights into autophagosome-lysosome fusion. J Cell Sci, 2017; 130: 1209-1216. doi: 10.1242/jcs.196352 [16] Bejarano E, Yuste A, Patel B, et al. Connexins modulate autophagosome biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol, 2014; 16: 401-414. doi: 10.1038/ncb2934 [17] Sinha M, Jang Y C, Oh J, et al. Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in mouse skeletal muscle. Science, 2014; 344: 649-652. doi: 10.1126/science.1251152 [18] Rajawat Y S, Hilioti Z, Bossis I. Aging: central role for autophagy and the lysosomal degradative system. Ageing Res Rev, 2009; 8: 199-213. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.05.001 [19] Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in aging, disease and death: the true identity of a cell death impostor. Cell Death Differ, 2009; 16: 1-2. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.139 [20] Carmona-Gutierrez D, Hughes A L, Madeo F, et al. The crucial impact of lysosomes in aging and longevity. Ageing Res Rev, 2016; 32: 2-12. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.04.009 [21] Guo B, Huang X, Zhang P, et al. Genome-wide screen identifies signaling pathways that regulate autophagy during Caenorhabditis elegans development. EMBO Rep, 2014; 15: 705-713. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338310 [22] Egerman M A, Glass D J. The role of GDF11 in aging and skeletal muscle, cardiac and bone homeostasis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 2019; 54: 174-183. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2019.1610722 [23] Kalka C, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Transplantation of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000; 97: 3422-3427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3422 [24] Pan Z, Sun X, Shan H, et al. MicroRNA-101 inhibited postinfarct cardiac fibrosis and improved left ventricular compliance via the FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene/transforming growth factor-β1 pathway. Circulation, 2012; 126: 840-850. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.094524 [25] Kawamoto A, Gwon H C, Iwaguro H, et al. Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation, 2001; 103: 634-637. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.5.634 [26] Masuda H, Iwasaki H, Kawamoto A, et al. Development of serum-free quality and quantity control culture of colony-forming endothelial progenitor cell for vasculogenesis. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2012; 1: 160-171. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0023 [27] Tang Y, Vater C, Jacobi A, et al. Salidroside exerts angiogenic and cytoprotective effects on human bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells via Akt/mTOR/p70S6K and MAPK signalling pathways. Br J Pharmacol, 2014; 171: 2440-2456. doi: 10.1111/bph.12611 [28] Yu M, Chen Y, Li X, et al. YAP1 contributes to NSCLC invasion and migration by promoting Slug transcription via the transcription co-factor TEAD. Cell Death Dis, 2018; 9: 464. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0515-z [29] Reines B, Cheng L I, Matzinger P. Unexpected regeneration in middle-aged mice. Rejuvenation Res, 2009; 12: 45-52. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0792 [30] Ikutomi M, Sahara M, Nakajima T, et al. Diverse contribution of bone marrow-derived late-outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells to vascular repair under pulmonary arterial hypertension and arterial neointimal formation. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2015; 86: 121-135. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.07.019 [31] Wang X, Wang R, Jiang L, et al. Endothelial repair by stem and progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2022; 163: 133-146. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.10.009 [32] Salybekov A A, Kobayashi S, Asahara T. Characterization of endothelial progenitor cell: past, present, and future. Int J Mol Sci, 2022; 23(14): 7697. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147697 [33] Altabas V, Altabas K, Kirigin L. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in ageing and age-related diseases: how currently available treatment modalities affect EPC biology, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular outcomes. Mech Ageing Dev, 2016; 159: 49-62. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2016.02.009 [34] Michaud S E, Dussault S, Haddad P, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells from healthy smokers exhibit impaired functional activities. Atherosclerosis, 2006; 187: 423-432. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.10.009 [35] Caiado F, Dias S. Endothelial progenitor cells and integrins: adhesive needs. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair, 2012; 5: 4. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-4 [36] Zenner H L, Collinson L M, Michaux G, et al. High-pressure freezing provides insights into Weibel-Palade body biogenesis. J Cell Sci, 2007; 120: 2117-2125. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007781 [37] Neumuller J, Neumuller-Guber S E, Lipovac M, et al. Immunological and ultrastructural characterization of endothelial cell cultures differentiated from human cord blood derived endothelial progenitor cells. Histochem Cell Biol, 2006; 126: 649-664. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0201-6 [38] Raposo G, Marks M S, Cutler D F. Lysosome-related organelles: driving post-Golgi compartments into specialisation. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2007; 19: 394-401. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.05.001 [39] Yang J, Yu J, Li D, et al. Store-operated calcium entry-activated autophagy protects EPC proliferation via the CAMKK2-MTOR pathway in ox-LDL exposure. Autophagy, 2017; 13: 82-98. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1245261 [40] Matsushita M, Suzuki N N, Obara K, et al. Structure of Atg5. Atg16, a complex essential for autophagy. J Biol Chem, 2007; 282: 6763-6772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609876200 [41] Hung H S, Yang Y C, Lin Y C, et al. Regulation of human endothelial progenitor cell maturation by polyurethane nanocomposites. Biomaterials, 2014; 35: 6810-6821. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.076 [42] Simon H U, Friis R, Tait S W, et al. Retrograde signaling from autophagy modulates stress responses. Sci Signal, 2017; 10. [43] Liu X, Rothe K, Yen R, et al. A novel AHI-1-BCR-ABL-DNM2 complex regulates leukemic properties of primitive CML cells through enhanced cellular endocytosis and ROS-mediated autophagy. Leukemia, 2017; 31: 2376-2387. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.108 [44] Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito V A, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science, 2011; 332: 1429-1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592 [45] Brunk U T, Terman A. Lipofuscin: mechanisms of age-related accumulation and influence on cell function. Free Radic Biol Med, 2002; 33: 611-619. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00959-0 [46] Mizunoe Y, Sudo Y, Okita N, et al. Involvement of lysosomal dysfunction in autophagosome accumulation and early pathologies in adipose tissue of obese mice, Autophagy, 2017; 13: 642-653. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1274850 [47] Zhang D, Chang S, Jing B, et al. Reactive oxygen species are essential for vasoconstriction upon cold exposure. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021; 2021: 8578452. doi: 10.1155/2021/8578452 [48] Ruperez C, Blasco-Roset A, Kular D, et al. Autophagy is involved in cardiac remodeling in response to environmental temperature change. Front Physiol, 2022; 13: 864427. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.864427 [49] Sun H J, Nie X W, Yu K Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of gasotransmitters for cold stress-related cardiovascular disease. Frigid Zone Medicine, 2022; 2(1): 10-24. doi: 10.2478/fzm-2022-0002 [50] Fan J F, Xiao Y C, Feng Y F, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cold exposure and cardiovascular disease outcomes. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2023; 10: 1084611. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1084611 [51] Francula-Zaninovic S, Nola I A. Management of measurable variable cardiovascular disease' risk factors. Curr Cardiol Rev, 2018; 14(3): 153-163. doi: 10.2174/1573403X14666180222102312 [52] Chen J, Xavier S, Moskowitz-Kassai E, et al. Cathepsin cleavage of sirtuin 1 in endothelial progenitor cells mediates stress-induced premature senescence. Am J Pathol, 2012; 180: 973-983. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.033 -

投稿系统

投稿系统

下载:

下载: