Association of point in range with β-cell function and insulin sensitivity of type 2 diabetes mellitus in cold areas

doi: 10.2478/fzm-2023-0031

-

Abstract:

Background and Objective Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) is crucial for achieving a glycemic target and upholding blood glucose stability, both of which are the primary purpose of anti-diabetic treatments. However, the association between time in range (TIR), as assessed by SMBG, and β-cell insulin secretion as well as insulin sensitivity remains unexplored. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the connections between TIR, derived from SMBG, and indices representing β-cell functionality and insulin sensitivity. The primary objective of this study was to elucidate the relationship between short-term glycemic control (measured as points in range [PIR]) and both β-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Methods This cross-sectional study enrolled 472 hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). To assess β-cell secretion capacity, we employed the insulin secretion-sensitivity index-2 (ISSI-2) and (ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index, while insulin sensitivity was evaluated using the Matsuda index and HOMA-IR. Since SMBG offers glucose data at specific point-in-time, we substituted TIR with PIR. According to clinical guidelines, values falling within the range of 3.9–10 mmol were considered "in range, " and the corresponding percentage was calculated as PIR. Results We observed significant associations between higher PIR quartiles and increased ISSI-2, (ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index, Matsuda index (increased) and HOMA-IR (decreased) (all P < 0.001). PIR exhibited positive correlations with log ISSI-2 (r = 0.361, P < 0.001), log (ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index (r = 0.482, P < 0.001), and log Matsuda index (r = 0.178, P < 0.001) and negative correlations with log HOMA-IR (r = -0.288, P < 0.001). Furthermore, PIR emerged as an independent risk factor for log ISSI-2, log (ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index, log Matsuda index, and log HOMA-IR. Conclusion PIR can serve as a valuable tool for assessing β-cell function and insulin sensitivity. -

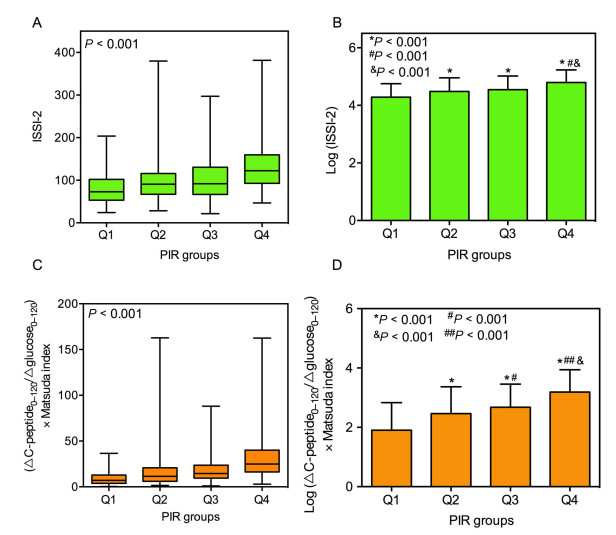

Figure 1. Different levels of insulin secretion-sensitivity index-2 (ISSI-2), logISSI-2, (ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index and log(ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index among patients with different point in range (PIR) quartiles. Comparisons of ISSI-2(A), logISSI-2(B), (ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index (C) and log(ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index (D) among patients with different PIR quartiles (Q1-Q4). P-value for the significant difference among the groups was determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test (A, C), one-way ANCOVA (B, D). Q1: PIR ≤ 51.5%, Q2: 51.5% < PIR ≤ 68.0%, Q3: 68.0% < PIR ≤ 80.0%, Q4: PIR > 80.0%. Data are presented as the median and interquartile range (25th–75th) (A, C), mean ± SD (B, D). P < 0.001 vs. group Q1; #P < 0.001 vs. group Q2; & P < 0.001 vs. group Q3 in panel B; P < 0.001 vs. group Q1; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.001 vs. group Q2; & P < 0.001 vs. group Q3 in panel D.

Figure 2. Different levels of Matsuda index and log Matsuda index among patients with different PIR quartiles. Comparisons of Matsuda index(A) and log Matsuda index(B) among patients with different point in range (PIR) quartiles (Q1-Q4). P-value for the significant difference among the groups was determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test (A), one-way ANCOVA (B). Q1: PIR ≤ 51.5%, Q2: 51.5% < PIR ≤ 68.0%, Q3: 68.0% < PIR ≤ 80.0%, Q4: PIR > 80.0%. Data are presented as the median and interquartile range (25th–75th) (A), mean ± SD (B). P < 0.001 vs. group Q1.

Figure 3. Different levels of HOMA-IR and log HOMA of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) among patients with different point in range (PIR) quartiles. Comparisons of HOMA-IR(A) and log HOMA-IR(B) among patients with different PIR quartiles (Q1-Q4). P-value for the significant difference among the groups was determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test(A), one-way ANCOVA(B). Q1: PIR ≤ 51.5%, Q2: 51.5% < PIR ≤ 68.0%, Q3: 68.0% < PIR ≤ 80.0%, Q4: PIR > 80.0%. Data are presented as the median and interquartile range (25th–75th) (A), mean ± SD (B). ***P < 0.001 vs. group Q1; #P < 0.05 vs. group Q2.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the participants according to PIR quartiles

Variables Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 P Age (years) 53.0 (47.0-62.0) 55.0 (46.0-64.0) 55.0 (47.0-61.5) 53.0 (43.0-60.0) 0.395 Male (n, %) 69.0 (61.6) 67.0 (51.5) 65.0 (54.2) 56.0 (50.9) 0.345 BMI (kg/m2) 25.0 (23.3-27.5) 25.4 (23.8-28.4) 25.5 (23.0-27.5) 26.1 (23.6-28.4) 0.203 Risk factors SBP (mmHg) 135.5 (125.5-149.0) 138.0 (125.0-151.0) 139.0 (124.0-150.0) 138.0 (124.0-153.0) 0.898 DBP (mmHg) 86.5 (78.0-95.5) 86.0 (79.0-93.0) 85.5 (79.0-97.0) 89.0 (82.0-95.0) 0.263 Current Smoking (n, %) 33.0 (29.5) 34.0 (26.2) 24.0 (20.0) 17.0 (15.5) 0.057 Current alcohol drinker (n, %) 20.0 (17.9) 13.0 (10.0) 17.0 (14.2) 11.0 (10.0) 0.221 Family history of diabetes (n, %) 21.0 (18.8) 27.0 (20.8) 16.0 (13.3) 18.0 (16.4) 0.451 Diabetes duration (years) (n, %) < 5 years 51.0 (45.5) 53.0 (40.8) 63.0 (52.5) 72.0 (65.4) 0.001 5-10 years 26.0 (23.2) 34.0 (26.1) 26.0 (21.7) 19.0 (17.3) 0.001 > 10 years 35.0 (31.3) 43.0 (33.1) 31.0 (25.8) 19.0 (17.3) 0.001 Laboratory data HbA1c (%) 10.2 (9.1-11.1) 9.6 (8.2-10.7) 8.7 (7.8-10.7) 8.3 (7.1-9.6) < 0.001 eGFR (mL/min) 94.0 (73.9-124.7) 96.4 (75.2-120.8) 101.8 (74.0-130.8) 104.6 (83.2-126.6) 0.270 TG (mmol/L) 2.07 (1.28-3.21) 1.78 (1.30-2.79) 1.76 (1.13-2.75) 1.67 (1.14-2.47) 0.089 TC (mmol/L) 4.98 (4.27-5.80) 4.69 (3.91-5.47) 4.84 (3.82-5.73) 5.04 (4.02-5.61) 0.204 HDL-C (mmol/L) 1.07 (0.92-1.26) 1.04 (0.90-1.19) 1.09 (0.90-1.27) 1.14 (1.01-1.33) 0.018 LDL-C (mmol/L) 3.03 (2.43-3.70) 2.85 (2.08-3.35) 2.65 (2.20-3.71) 2.95 (2.20-3.67) 0.216 Data are expressed as the median and interquartile range (25th–75th) for variables without a normal distribution. Categorical data are expressed as frequency and percentage. Between the four groups, the P-values were calculated using Wilcoxon rank sum test. BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; PIR: point in range; SBP: systolic blood pressure. Table 2. Multiple linear regression models for logISSI-2 and log(ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index

Variables β standardized regression coefficient P-value For logISSI-2 PIR (%) 0.110 0.243 < 0.001 Diabetes duration (years) -0.120 -0.206 < 0.001 HbA1c (%) -0.054 -0.209 < 0.001 LDL-C (mmol/L) -0.064 -0.125 0.001 For log(ΔC-peptide0–120/Δglucose0–120) × Matsuda index PIR (%) 0.269 0.307 < 0.001 Diabetes duration (years) -0.231 -0.206 < 0.001 HbA1c (%) -0.165 -0.329 < 0.001 eGFR (mL/min) 0.002 0.104 0.015 TC (mmol/L) -0.059 -0.078 0.043 eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; ISSI-2: insulin secretion-sensitivity index-2; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PIR: point in range; TC: total cholesterol. Table 3. Multiple linear regression models for log Matsuda index

Variables β standardized regression coefficient P-value PIR (%) 0.076 0.166 < 0.001 Male (%) -0.156 -0.157 < 0.001 BMI (kg/m2) -0.035 -0.252 < 0.001 TG (mmol/L) -0.032 -0.163 < 0.001 HDL-C (mmol/L) 0.214 0.119 0.011 LDL-C (mmol/L) -0.049 -0.096 0.030 BMI: body mass index; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PIR: point in range; TG: triglyceride. Table 4. Multiple linear regression models for log HOMA-IR

Variables β standardized regression coefficient P-value PIR (%) -0.146 -0.269 < 0.001 Male (%) 0.107 0.089 0.039 BMI (kg/m2) 0.036 0.215 < 0.001 TC (mmol/L) 0.079 0.169 < 0.001 HDL-C (mmol/L) -0.357 -0.167 < 0.001 BMI: body mass index; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC: total cholesterol; HOMA-IR: HOMA of insulin resistance; PIR: point in range. -

[1] Porte D. β-cells in type Ⅱ diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, 1991; 40(2): 166–180. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.166 [2] Defronzo R A. Lilly lecture 1987. The triumvirate: Beta-cell, muscle, liver. A collusion responsible for NIDDM. Diabetes, 1988; 37(6): 667-687. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.6.667 [3] Stratton I M, Adler A I, Neil H A, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ, 2000; 321(7258): 405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405 [4] Kramer C K, Choi H, Zinman B, et al. Glycemic variability in patients with early type 2 diabetes: the impact of improvement in β-cell function. Diabetes Care, 2014; 37(4): 1116–1123. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2591 [5] Liu L, Liu J, Xu L, et al. Lower mean blood glucose during short-term intensive insulin therapy is associated with long-term glycemic remission in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: Evidence-based recommendations for standardization. J Diabetes Investig, 2018; 9(4): 908–916. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12782 [6] Rohlfing C L, Wiedmeyer H M, Little R R, et al. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA1c: analysis of glucose profiles and HbA1c in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care, 2002; 25(2): 275–278. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.275 [7] Nitin S. HbA1c and factors other than diabetes mellitus affecting it. Singapore Med J, 2010; 51(8): 616–22. PMID: 20848057. [8] Lu J, Ma X, Zhou J, et al. Association of time in range, as assessed by continuous glucose monitoring, with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2018; 41(11): 2370–2376. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1131 [9] García-Lorenzo B, Rivero-Santana A, Vallejo-Torres L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of real-time continuous monitoring glucose compared to self-monitoring of blood glucose for diabetes mellitus in Spain. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr, 2018; 65(7): 380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.endinu.2018.03.008 [10] Young L A, Buse J B, Weaver M A, et al. Glucose self-monitoring in non-insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med, 2017; 177(7): 920–929. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1233 [11] Cutruzzolà A, Irace C, Parise M, et al. Time spent in target range assessed by self-monitoring blood glucose associates with glycated hemoglobin in insulin treated patients with diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2020; 30(10): 1800–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.06.009 [12] The Diabetes Research in Children Network DirecNet Study Group. Eight-point glucose testing versus the continuous glucose monitoring system in evaluation of glycemic control in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2005; 90(6): 3387–3391. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2510 [13] Brackney, Elisabeth D. Enhanced self-monitoring blood glucose in non-insulin requiring Type 2 diabetes: A qualitative study in primary care. J Clin Nurs, 2018; 27(9-10): 2120–2131. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14369 [14] Kohnert K D, Augstein P, Zander E, et al. Glycemic variability correlates strongly with postprandial beta-cell dysfunction in a segment of type 2 diabetic patients using oral hypoglycemic agents. Diabetes Care, 2009; 32(6): 1058–1062. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1956 [15] Inker L A, Schmid C H, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med, 2012; 367(1): 20–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248 [16] Kramer C K, Choi H, Zinman B, et al. Determinants of reversibility of β-cell dysfunction in response to short-term intensive insulin therapy in patients with early type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2013; 305(11): E1398–E1407. . doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00447.2013 [17] Retnakaran R, Shen S, Hanley A J, et al. Hyperbolic relationship between insulin secretion and sensitivity on oral glucose tolerance test. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2008; 16(8): 1901–1907. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.307 [18] Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Goran M I, et al. Evaluation of proposed oral disposition index measures in relation to the actual disposition index. Diabet Med, 2009; 26(12): 1198–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02841.x [19] Matsuda M, DeFronzo R A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care, 1999; 22(9): 1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462 [20] Matthews D R, Hosker J P, Rudenski A S, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia, 1985; 28(7): 412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883 [21] Defronzo R A, Tripathy D, Schwenke D C, et al. Prediction of diabetes based on baseline metabolic characteristics in individuals at high risk. Diabetes Care, 2013; 36(11): 3607–3612. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0520 [22] Beck R W, Bergenstal R M, Riddlesworth T D, et al. Validation of time in range as an outcome measure for diabetes clinical trials. Diabetes care, 2019; 42(3): 400–405. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1444 [23] Klatman E L, Jenkins A J, Ahmedani M Y, et al. Blood glucose meters and test strips: global market and challenges to access in low-resource settings. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2019; 7(2): 150–160. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30074-3 [24] Weinstock R S, Braffett B H, McGuigan P, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in youth-onset type 2 diabetes: results from the TODAY study. Diabetes Care, 2019; 42(5): 903–909. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1854 [25] Schnell O, Klausmann G, Gutschek B, et al. Impact on diabetes self-management and glycemic control of a new color-based SMBG meter. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 2017; 11(6): 1218–1225. doi: 10.1177/1932296817706376 [26] Zhang Y, Dai J, Han X, et al. Glycemic variability indices determined by self-monitoring of blood glucose are associated with β-cell function in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2020; 164: 108152. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108152 [27] Kilpatrick E S, Rigby A S, Goode K, et al. Relating mean blood glucose and glucose variability to the risk of multiple episodes of hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia, 2007; 50(12): 2553-2561. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0820-z [28] Schnell O, Barnard K, Bergenstal R, et al. Clinical utility of SMBG: recommendations on the use and reporting of SMBG in clinical research. Diabetes Care, 2015; 38(9): 1627–1633. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2919 [29] Swisa A, Glaser B, Dor Y. Metabolic stress and compromised identity of pancreatic beta cells. Front Genet, 2017; 8: 21. [30] Veres A, Faust A L, Bushnell H L, et al. Charting cellular identity during human in vitro β-cell differentiation. Nature, 2019; 569(7756): 368–373. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1168-5 [31] Sun J, Ni Q, Xie J, et al. β-Cell dedifferentiation in patients with T2D with adequate glucose control and nondiabetic chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2019; 104(1): 83–94. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00968 [32] Wang Z, York N W, Nichols C G, et al. Pancreatic β-cell dedifferentiation in diabetes and redifferentiation following insulin therapy. Cell Metab, 2014; 19(5): 872–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.010 [33] Murata M, Adachi H, Oshima S, et al. Glucose fluctuation and the resultant endothelial injury are correlated with pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2017; 131: 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.07.007 [34] Wu N, Shen H, Liu H, et al. Acute blood glucose fluctuation enhances rat aorta endothelial cell apoptosis, oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in vivo. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2016; 15(1): 109. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0427-0 [35] Kahn S E, Prigeon R L, McCulloch D K, et al. Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and β-cell function in human subjects: evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes, 1993; 42: 1663-1667. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1663 [36] Wang T, Lu J, Shi L, et al. Association of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction with incident diabetes among adults in China: a nationwide, population-based, prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2020; 8(2): 115–124. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30425-5 [37] Keane K N, Cruzat V F, Carlessi R, et al. Molecular events linking oxidative stress and inflammation to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2015; 2015: 181643. [38] Weng J, Li Y, Xu W, et al. Effect of intensive insulin therapy on β-cell function and glycaemic control in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a multicentre randomised parallel-group trial. Lancet, 2008; 371(9626): 1753–1760. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60762-X [39] Ma M, Liu H, Yu J. Triglyceride is independently correlated with insulin resistance and islet beta cell function: a study in population with different glucose and lipid metabolism states. Lipids Health Dis, 2020; 19(1): 121. doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-01303-w [40] Fiorentino T V, Succurro E, Marini M A, et al. HDL cholesterol is an independent predictor of β-cell function decline and incident type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 2020; 36(4): e3289. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3289 [41] Rutti S, Ehses J A, Sibler R A, et al. Low and high-density lipoproteins modulate function, apoptosis and proliferation of primary human and murine pancreatic beta cells. Endocrinology, 2009; 150: 4521–4530. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0252 [42] Young K A, Maturu A, Lorenzo C, et al. The triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein choles-terol (TG/HDL-C) ratio as a predictor of insulin resistance, b-cell function, and diabetes in His-panics and African Americans. J Diabetes Complications, 2019; 33: 118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.10.018 [43] Ochoa-Rosales C, Portilla-Fernandez E, Nano J, et al. Epigenetic link between statin therapy and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2020; 43(4): 875–884. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1828 [44] Yang Y M, Shin B C, Son C, et al. An analysis of the associations between gender and metabolic syndrome components in Korean adults: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord, 2019; 19(1): 67. doi: 10.1186/s12902-019-0393-0 [45] Arslanian S, Bacha F, Grey M, et al. Evaluation and management of youth-onset type 2 diabetes: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 2018; 41(12): 2648–2668. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0052 [46] Hope S V, Knight B A, Shields B M, et al. Random non-fasting C-peptide: bringing robust assessment of endogenous insulin secretion to the clinic. Diabet Med, 2016; 33(11): 1554–1558. doi: 10.1111/dme.13142 [47] Arslanian S, El Ghormli L, Bacha F, et al. Adiponectin, insulin sensitivity, β-cell function, and racial/ethnic disparity in treatment failure rates in TODAY. Diabetes Care, 2017; 40(1): 85–93. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0455 -

fzm-3-4-242_ESM.pdf

fzm-3-4-242_ESM.pdf

-

投稿系统

投稿系统

下载:

下载: