Changes of calcitonin gene-related peptide and other serological indicators in vestibular migraine patients

doi: 10.2478/fzm-2021-0014

-

Abstract:

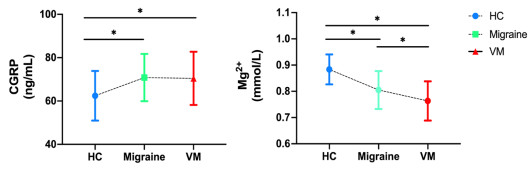

Objective It aims to evaluate the diagnostic ability of CGRP and other blood indicators in vestibular migraine (VM) patients, and to explain the potential pathological effects of these biomarkers. The hypothesis of VM being a variant of migraine was examined. Methods A total of 32 VM patients, 35 migraine patients, and 30 healthy control subjects (HC) were selected for this cross-sectional study. Detailed statistics on demographic data, clinical manifestations, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and common clinical laboratory indicators were measured within 24 hours from the onset of the conditions. Receptor operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC) were analyzed for biomarkers. The risk factors of VM and migraine were determined through univariate and multivariate analyses. Results Compared with HC, serum CGRP levels (p(VM) = 0.012, p(Migraine) = 0.028) increased and Mg2+ levels (p(VM) < 0.001, p (Migraine) < 0.001) deceased in VM patients and migraine patients. In multiple logistic regression, VM was correlated with CGRP [odds ratio (OR) = 1.07; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.02-1.12; P = 0.01] and Mg2+ [odds ratio (OR) = 0.03; 95% CI, 0.07-0.15; P < 0.001)]. Migraine was correlated with CGRP [odds ratio (OR) = 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12; P = 0.01] and Mg2+ [odd ratio (OR = 0.01; 95% CI, 0-0.02; P < 0.001)]. Mg2+ discriminated good differentiation between VM and migraine groups, with AUC of 0.649 (95% CI, 0.518 to 0.780). The optimal threshold for Mg2+ to diagnose VM was 0.805. Conclusions This study demonstrated that CGRP and Mg2+ may be promising laboratory indicators to discriminate HC from VM/migraine, while Mg2+ may be uded as a discriminator between VM and migraine. -

Table 1. Demographical, physiological, and clinical characteristics of vestibular migraine (VM) patients, migraine patients and control healthy (n = 97)

Variables HC (N = 30) Migraine (N = 35) VM (N = 32) ANOVA P Demographic characteristics Gender (Male/Female) 14/16 14/21 12/20 0.703d Age (years) 49.90±7.25 47.86±9.00 52.52±8.06 0.068 Risk factors Smoking(percentage) 2(6.67) 3(8.57) 5(15.162) 0.498 Drinking(percentage) 2(6.67) 3(8.57) 4(12.5) 0.746 Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 127.93±10.68 126.43±15.89 134.15±19.68 0.118 Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 79.57±7.60 78.54±13.79 80.05±10.97 0.732 Laboratory test indicators CGRP (pg/mL) 62.41±11.46 70.82±10.90b 70.45±12.27c 0.007* Mg2+(mmol/L) 0.88±0.06 0.81±0.07b 0.76±0.07ac < 0.001* Red blood cell (1012/L) 4.68±0.49 4.71±0.51 4.72±0.52 0.444 Platelet (109/L) 230.44±70.21 253.94±54.79 254.36±52.42 0.210 Blood glucose (mmol/L) 5.73±0.46 5.69±1.21 5.31±1.35 0.264 Cholesterol (mmol/L) 5.10±0.95 4.96±1.06 5.22±0.73 0.521 Triglyceride (mmol/L) 1.85±1.40 1.91±1.50 1.76±1.28 0.817 Data are expressed as mean±SD. Abbreviations: CGRP, Calcitonin gene-related peptide; Mg2+, Magnesium ions. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test.a, P < 0.05 VM vs. control; b P < 0.05 migraine patients vs. control; c, P < 0.05 VM vs. migraine patients; d, Chi-square test; *, ANOVA P < 0.05. Table 2. Summary of clinical characteristics of the VM and migraine patients included in the present study

Variables Migraine (N = 35) VM (N = 32) P value Symptoms Frequency (number of times) 2.14±1.14 1.34±0.86 0.002* Duration(hours) 15.59±17.40 8.30±11.57 0.050* Accompanying symptoms Nausea 22(62.86) 24(75) 0.285b Vomiting 14(40) 18(56.25) 0.183b Tinnitus 0(0) 5(15.63) 0.015b* Blurred vision 7(20) 3(9.4) 0.223b Defecation 0(0) 1(3.1) 0.292b Comorbidities Arterial hypertension 8(22.86) 14(43.75) 0.069b Depression 4(11.43) 2(6.25) 0.458b Data are expressed as mean±SD. Values are shown as number (percentage) except where specified. *P < 0.05; a two sample t-test; b Chi-squared test. Table 3. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses between VM patients and migraine patients

Variables VM Migraine Univariate Multivariate Univariate Multivariate OR (95% CIs) P value OR (95% CIs) P value OR (95% CIs) P value OR (95% CIs) P value Age 1.06

(1.01-1.12)0.03* 1.04

(0.98-1.11)1.04 0.95

(0.90-1.00)0.06 0.97

(0.91-1.03)0.35 Gender 1.216

(0.51-2.91)0.66 1.52

(0.54-4.08)1.52 1.04

(0.45-2.43)0.93 1.30

(0.48-3.55)0.61 Current smoking 0

(0-)0.99 1.012

(0.26-2.66)0.11 5.63

(0.56-56.3)0.14 2.53

(0.25-25.77)0.43 Current drinking 0.48

(0.05-4.52)0.52 0.84

(0.44-17.42)0.43 2.77

(0.05-25.77)0.28 2.53

(0.25-25.77)0.44 Frequency

(number of times)1.43

(1.24-1.78)0.01* - 2.31

(1.29-4.16)0.01* - Duration

(hours)0.96

(0.92-1.00)0.07 - 1.04

(1.00-1.09)0.07 - Nausea 1.57

(0.54-4.53)0.41 - 0.64

(0.22-1.85)0.41 - Vomiting 1.93

(0.73-5.10)0.19 - 0.52

(0.20-1.37)0.19 - Tinnitus 1.12

(0.32-3.89)0.86 - 0.90

(0.36-3.13)0.86 - Defecation 2.27

(0.20-26.27)0.51 - 0.44

(0.34-5.11)0.51 - CGRP 1.01

(0.98-1.05)0.46 1.07

(1.02-1.12)0.01* 1.03

(0.99-1.07)0.11 1.07

(1.02-1.12)0.01* Mg2+ 0

(0-0.002)< 0.001* 0.03

(0.07-0.15)< 0.001* 0.15

(0-21.76)0.45 0.01

0(0-0.02)< 0.001* Note: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; Mg2+, Magnesium ions. *, P < 0.01. Table 4. ROC analysis results (AUC and Youden indices) for VM patients, migraine patients and control subjects

Variables AUC value p value 95% CI Youden index Optimal threshold CGRP Migraine vs. HC 0.694 0.009* (0.563, 0.825) 0.364 55.655 ng/ml VM vs. HC 0.680 0.016* (0.545, 0.815) 0.357 54.15 ng/ml Migraine vs. VM 0.531 0.663 (0.391-0.670) 0.132 59.365 ng/ml Mg2+ Migraine vs. HC 0.812 < 0.001* (0.706-0.919) 0.55 0.885 mmol/l VM vs. HC 0.907 < 0.001* (0.837, 0.978) 0.687 0.805 mmol/l Migraine vs. VM 0.649 0.035* (0.518, 0.780) 0.244 0.805 mmol/l Abbreviations: CGRP, Calcitonin gene-related peptide; Mg2+, Magnesium ions; AUC, Area Under Curve; CI, Confidence interval. -

[1] Li V, McArdle H, Trip S A. Vestibular migraine. BMJ, 2019; 366: l4213. [2] Xia J, Kong W J, Zhu Y, et al. Intrinsic membrane properties of rat medial vestibular nucleus neurons and their responses to simulated vestibular input signals. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2008; 43(10): 767-772. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19119674 [3] Neuhauser H K, Radtke A, Von Brevern M, et al. Migrainous vertigo: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Neurology, 2006; 67(6): 1028-1033. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237539.09942.06 [4] Fernandez M, Birdi J S, Irving G J, et al. Pharmacological agents for the prevention of vestibular migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015; 6: CD010600. [5] Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res, 2012; 22(4): 167-172. doi: 10.3233/VES-2012-0453 [6] Alghadir A H, Anwer S. Effects of vestibular rehabilitation in the management of a vestibular migraine: a review. Front Neurol, 2018; 9: 440. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00440 [7] Zhou C, Zhang L, Jiang X, et al. A novel diagnostic prediction model for vestibular migraine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2020; 16: 1845-1852. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S255717 [8] Cuccurazzu B, Halberstadt A L. Projections from the vestibular nuclei and nucleus prepositus hypoglossi to dorsal raphe nucleus in rats. Neurosci Lett, 2008; 439(1): 70-74. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.094 [9] Warfvinge K, Edvinsson L. Distribution of CGRP and CGRP receptor components in the rat brain. Cephalalgia, 2019; 39(3): 342-353. doi: 10.1177/0333102417728873 [10] Tajti J, Uddman R, Edvinsson L. Neuropeptide localization in the "migraine generator" region of the human brainstem. Cephalalgia, 2001; 21(2): 96-101. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00140.x [11] Tiller-Borcich J K, Capili H, Gordan G S. Human brain calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is concentrated in the locus caeruleus. Neuropeptides, 1988; 11(2): 55-61. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(88)90010-8 [12] Emeson R B, Hedjran F, Yeakley J M, et al. Alternative production of calcitonin and CGRP mRNA is regulated at the calcitonin-specific splice acceptor. Nature, 1989; 341(6237): 76-80. doi: 10.1038/341076a0 [13] Tanaka M, Takeda N, Senba E, et al. Localization and origins of calcitonin gene-related peptide containing fibres in the vestibular end-organs of the rat. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl, 1989; 468: 31-34. doi: 10.3109/00016488909139017 [14] Van Rossum D, Hanisch U K, Quirion R. Neuroanatomical localization, pharmacological characterization and functions of CGRP, related peptides and their receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 1997; 21(5): 649-678. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(96)00023-1 [15] Xanthos D N, Sandkuhler J. Neurogenic neuroinflammation: inflammatory CNS reactions in response to neuronal activity. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2014; 15(1): 43-53. doi: 10.1038/nrn3617 [16] De Hoon J N, Pickkers P, Smits P, et al., Calcitonin gene-related peptide: exploring its vasodilating mechanism of action in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2003; 73(4): 312-321. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00007-9 [17] Sarchielli P, Pini L A, Zanchin G, et al., Clinical-biochemical correlates of migraine attacks in rizatriptan responders and non-responders. Cephalalgia, 2006; 26(3): 257-265. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01016.x [18] Hsu L C, Wang S J, Fuh J L. Prevalence and impact of migrainous vertigo in mid-life women: a community-based study. Cephalalgia, 2011; 31(1): 77-83. doi: 10.1177/0333102410373152 [19] Han D. Association of serum levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide and cytokines during migraine attacks. Ann Indian Acad Neurol, 2019; 22(3): 277-281. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_371_18 [20] Cernuda-Morollon E, Larrosa D, Ramon C, et al. Interictal increase of CGRP levels in peripheral blood as a biomarker for chronic migraine. Neurology, 2013; 81(14): 1191-1196. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a6cb72 [21] Olesen J, Diener H C, Husstedt I W, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist BIBN 4096 BS for the acute treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med, 2004; 350(11): 1104-1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030505 [22] Hoffmann J, Goadsby P J. New agents for acute treatment of migraine: cgrp receptor antagonists, inos inhibitors. Curr Treat Options Neurol, 2012; 14(1): 50-59. doi: 10.1007/s11940-011-0155-4 [23] Villalon C M, Olesen J. The role of CGRP in the pathophysiology of migraine and efficacy of CGRP receptor antagonists as acute antimigraine drugs. Pharmacol Ther, 2009; 124(3): 309-323. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.09.003 [24] Ho T W, Edvinsson L, Goadsby P J. CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol, 2010; 6(10): 573-582. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.127 [25] Akerman S, Romero-Reyes M, Holland P R. Current and novel insights into the neurophysiology of migraine and its implications for therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther, 2017; 172: 151-170. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.12.005 [26] Russo A F. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): a new target for migraine. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2015; 55(1): 533-552. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124701 [27] Olesen J, Burstein R, Ashina M, et al. Origin of pain in migraine: evidence for peripheral sensitisation. Lancet Neurol, 2009; 8(7): 679-690. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70090-0 [28] Akerman S, Holland P R, Summ O, et al. A translational in vivo model of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: therapeutic characterization. Brain, 2012; 135(Pt 12): 3664-3675. [29] Burstein R, Jakubowski M, Garcia-Nicas E, et al., Thalamic sensitization transforms localized pain into widespread allodynia. Ann Neurol, 2010; 68(1): 81-91. doi: 10.1002/ana.21994 [30] Sixt M L, Messlinger K, Fischer M J. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist olcegepant acts in the spinal trigeminal nucleus. Brain, 2009; 132(Pt 11): 3134-3141. http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/awp168v1.pdf [31] Rossi C, Alberti A, Sarchielli P, et al. Balance disorders in headache patients: evaluation by computerized static stabilometry. Acta Neurol Scand, 2005; 111(6): 407-413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00422.x [32] Akdal G, Donmez B, Ozturk v, et al. Is balance normal in migraineurs without history of vertigo? Headache, 2009; 49(3): e419-e425. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01256.x [33] Anagnostou E, Gerakoulis S, Voskou P, et al. Postural instability during attacks of migraine without aura. Eur J Neurol, 2019; 26(2): 319-321. doi: 10.1111/ene.13815 [34] Balaban C D. Migraine, vertigo and migrainous vertigo: Links between vestibular and pain mechanisms. J Vestib Res, 2011; 21(6): 315-321. doi: 10.3233/VES-2011-0428 [35] Balaban C D, Jacob R G, Furman J M. Neurologic bases for comorbidity of balance disorders, anxiety disorders and migraine: neurotherapeutic implications. Expert Rev Neurother, 2011; 11(3): 379-394. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.19 [36] Halberstadt A L, Balaban C D. Serotonergic and nonserotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus send collateralized projections to both the vestibular nuclei and the central amygdaloid nucleus. Neuroscience, 2006; 140(3): 1067-1077. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.053 [37] Goadsby P J, Lipton R B, Ferrari M D. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med, 2002; 346(4): 257-270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010917 [38] De Lacalle S, Saper C B. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-like immunoreactivity marks putative visceral sensory pathways in human brain. Neuroscience, 2000; 100(1): 115-130. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00245-1 [39] Richter F, Bauer R, Lehmenkuhler A, et al., Spreading depression in the brainstem of the adult rat: electrophysiological parameters and influences on regional brainstem blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2008; 28(5): 984-994. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600594 [40] May A, Goadsby P J. The trigeminovascular system in humans: pathophysiologic implications for primary headache syndromes of the neural influences on the cerebral circulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 1999; 19(2): 115-127. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199902000-00001 [41] Veronese N, Zanforlini B M, Manzato E, et al. Magnesium and healthy aging. Magnes Res, 2015; 28(3): 112-115. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2015.0387 [42] Arnaud M J. Update on the assessment of magnesium status. Br J Nutr, 2008; 99(Suppl 3): S24-S36. http://www.onacademic.com/detail/journal_1000036815339910_e2a5.html [43] Volpe S L. Magnesium in disease prevention and overall health. Adv Nutr, 2013; 4(3): S378-S383. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003483 [44] Lingam I, Robertson N J. Magnesium as a neuroprotective agent: a review of its use in the fetus, term infant with neonatal encephalopathy, and the adult stroke patient. Dev Neurosci, 2018; 40(1): 1-12. doi: 10.1159/000484891 [45] Köseoglu E, Talaslioglu A, Gönül A S, et al. The effects of magnesium prophylaxis in migraine without aura. Magnes Res, 2008; 21(2): 101-108. http://mineralmed.com.pt/documentos/pdf/3a24d700-574f-4b89-a0d9-dce7673c0681.pdf [46] Lodi R, IOTTI S, Cortelli P, et al. Deficient energy metabolism is associated with low free magnesium in the brains of patients with migraine and cluster headache. Brain Res Bull, 2001. 54(4): 437-441. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00440-3 [47] Coan E J, Collingridge G L. Magnesium ions block an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated component of synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett, 1985; 53(1): 21-26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90091-6 [48] Myrdal U, Leppert J, Edvinsson L, et al. Magnesium sulphate infusion decreases circulating calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in women with primary Raynaud's phenomenon. Clin Physiol, 1994; 14(5): 539-546. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.1994.tb00412.x [49] Innerarity S. Hypomagnesemia in acute and chronic illness. Crit Care Nurs Q, 2000; 23(2): 1-19; quiz 87. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200008000-00002 [50] Foster A C, Fagg G E. Neurobiology. Taking apart NMDA receptors. Nature, 1987; 329(6138): 395-396. doi: 10.1038/329395a0 [51] Sato K, Momose-Sato Y. Optical detection of developmental origin of synaptic function in the embryonic chick vestibulocochlear nuclei. J Neurophysiol, 2003; 89(6): 3215-3224. doi: 10.1152/jn.01169.2002 [52] Yuan H, Liu H, Hui H F, et al. Climatic variations and vertigo diseases in outpatients clinic of ENT. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2021; 35(2): 101-104. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/349096328_Climatic_variations_and_vertigo_diseases_in_outpatients_clinic_of_ENT [53] McCoy E S, Taylor-Blake B, Street S E, et al., Peptidergic CGRPalpha primary sensory neurons encode heat and itch and tonically suppress sensitivity to cold. Neuron, 2013; 78(1): 138-151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.030 [54] McCoy E S, Zylka M J. Enhanced behavioral responses to cold stimuli following CGRPalpha sensory neuron ablation are dependent on TRPM8. Mol Pain, 2014; 10: 69. http://mpx.sagepub.com/content/10/1744-8069-10-69.full.pdf [55] Nassini R, Materazzi S, Benemei S, et al. The TRPA1 channel in inflammatory and neuropathic pain and migraine. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol, 2014; 167: 1-43. http://download.e-bookshelf.de/download/0003/9272/70/L-G-0003927270-0013264025.pdf -

投稿系统

投稿系统

下载:

下载: