Clinical study of a new nutritional index for predicting long-term prognosis in patients with coronary atherosclerotic heart disease following percutaneous coronary intervention

doi: 10.1515/fzm-2024-0016

-

Abstract:

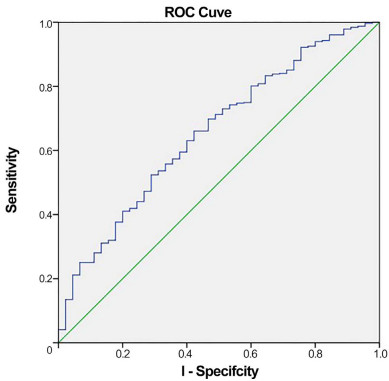

Background and Objective Some patients continue to experience major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in frigid places. Indexes of inflammation and nutrition alone were shown to predict outcomes in patients with PCI. However, the clinical predictive value of mixed indicators is unclear. This study aimed to assess the predictive value of the albumin/neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) on the long-term prognosis of patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Methods A total of 608 post-PCI CHD patients were categorized into low- and high-index groups based on the optimal cut-off values for albumin and NLR. The primary outcome was a composite endpoint comprising all-cause mortality and major adverse cerebrovascular events. The secondary outcome was the comparison of the predictive efficiency of the new nutritional index, albumin/NLR, with that of albumin or NLR alone. Results Over the five-year follow-up period, 45 patients experienced the composite endpoint. The incidence of endpoint events was significantly higher in the low-index group (12%) compared to the high-index group (4.9%). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed that the albumin/NLR index had a larger area under the curve (AUC: 0.655) than albumin (AUC: 0.621) or NLR (AUC: 0.646), indicating superior predictive efficiency. The prognostic nutritional index had an AUC of 0.644, further supporting the enhanced predictive value of the albumin/NLR index over individual nutritional and inflammatory markers. Conclusion The albumin/neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is independently associated with the long-term prognosis of CHD patients post-PCI and demonstrates superior predictive efficiency compared to individual nutritional and inflammatory markers. -

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier and cumulative hazard curves.

(A) The Kaplan–Meier curve displays survival time (in months) on the horizontal axis and the cumulative survival rate on the vertical axis. (B) The cumulative risk curve shows time to event (in months) on the horizontal axis and the cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) on the vertical axis. Log-rank analysis indicates a significant difference (P = 0.001).

Table 1. Comparison of general characteristics between the low- and high-index groups

Characteristics Total (N = 608) Low-index group (N = 217) High-index group (N = 391) P-value Age, years 59.50 (52.25, 66.00) 61.00 (55.00, 69.00) 58.00 (52.00, 65.00) < 0.001 Sex Male 406 (66.8) 147 (67.7) 259 (66.2) 0.706 Female 202 (33.2) 70 (32.3) 132 (33.8) 0.294 Smokingx Yes 235 (38.7) 88 (40.6) 147 (37.6) 0.473 No 373 (61.3) 129 (59.4) 244 (62.4) 0.527 Other comorbiditiesx Hypertension 343 (56.4) 117 (53.9) 226 (57.8) 0.355 Diabetes mellitus 158 (26.0) 59 (27.2) 99 (25.3) 0.615 Heart failure 60 (9.9) 43 (19.8) 17 (4.3) < 0.001 Stroke 117 (19.2) 45 (20.7) 72 (18.4) 0.486 Myocardial infarction 45 (7.4) 17 (7.8) 28 (7.2) 0.761 Drug usex ACEI/ARB 221 (36.3) 88 (40.6) 133 (34.0) 0.108 Beta receptor antagonist 336 (55.3) 128 (59.0) 208 (53.2) 0.169 CCB 203 (33.4) 59 (27.2) 144 (36.8) 0.016 Values are presented as number (%), unless otherwise stated; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor antagonist; CCB, calcium channel blocker. Table 2. Comparison of routine laboratory indices and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) between the low- and high-index groups

Characteristics Total (N = 608) Low-index group (N = 217) High-index group (N = 391) P-value Laboratory parameters Triglycerides 1.60 (1.21, 2.30) 1.51 (1.18, 2.03) 1.67 (1.25, 2.50) 0.004 Total cholesterol 4.51 (3.81, 5.31) 4.50 (3.86, 5.17) 4.53 (3.80, 5.36) 0.320 LDL 2.72 (2.16, 3.30) 2.75 (2.18, 3.28) 2.72 (2.16, 3.30) 0.728 HDL 1.07 (0.94, 1.26) 1.04 (0.92, 1.22) 1.09 (0.95, 1.26) 0.058 Trioxypurine 343.45 (288.75, 404.75) 348.20 (289.30, 406.60) 341.60 (288.60, 403.00) 0.726 GFR 91.72 (79.15, 105.93) 92.23 (75.22, 108.01) 91.27 (80.19, 105.48) 0.790 Serum albumin 43.78 ± 3.42 42.24 ± 3.59 44.63 ± 3.00 < 0.001 Neutrophil count 4.07 (3.21, 5.18) 5.34 (4.28, 6.44) 3.57 (2.93, 4.36) < 0.001 Lymphocyte count 1.95 (1.55, 2.40) 1.51 (1.18, 1.85) 2.19 (1.79, 2.59) < 0.001 Healthy nutritional status BMI 25.35 (23.18, 27.46) 25.18 (22.55, 27.55) 25.35 (23.44, 27.43) 0.351 Imageological examination LVEF, % 59.00 (57.00, 60.00) 58.00 (56.00, 60.00) 59.00 (58.00, 60.00) < 0.001 LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; BMI, body mass index. Table 3. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for all-cause mortality and MACCE

Variables Single-factor analysis Multiple-factor analysis HR 95% CI P-value HR 95% CI P-value Age 1.509 1.026-1.094 < 0.001 1.038 1.003-1.074 0.033 Hypertension 0.512 0.269-0.976 0.042 0.662 0.326-1.345 0.254 Heart failure 2.375 1.144-4.930 0.020 1.092 0.405-2.942 0.862 Myocardial infarction 0.265 0.131-0.535 < 0.001 0.415 0.179-0.961 0.040 ACEI/ARB 0.364 0.201-0.661 0.001 0.531 0.275-1.026 0.059 GFR 0.974 0.960-0.988 < 0.001 0.988 0.973-1.002 0.091 LVEF 0.932 0.894-0.971 0.001 0.977 0.922-1.036 0.433 Low-index group 2.584 1.430-4.670 0.002 2.179 1.163-4.080 0.015 MACCE, major unconscionable cerebrovascular events; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor antagonist; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. -

[1] Barquera S, Pedroza-Tobías A, Medina C, et al. Global overview of the epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Arch Med Res, 2015; 46 (5): 328-338. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.06.006 [2] Liu T D, Zheng Y Y, Tang J N, et al. Prognostic nutritional index as a novel predictor of Long-Term prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost, 2022; 28: 1-8 [3] Wada H, Dohi T, Miyauchi K, et al. Relationship between the prognostic nutritional index and long-term clinical outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Cardiol, 2018; 72 (2): 155-161. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.01.012 [4] Fan Y, He L, Zhou Y, et al. Predictive value of geriatric nutritional risk index in patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Front Nutr, 2021; 8: 736884. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.736884 [5] Chen L, Huang Z, Lu J, et al. Impact of the malnutrition on mortality in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Interv Aging, 2021; 16: 1347-1356. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S308569 [6] Wada H, Dohi T, Miyauchi K, et al. Prognostic impact of the geriatric nutritional risk index on long-term outcomes in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol, 2017; 119 (11): 1740-1745. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.051 [7] Liu J, Huang Z, Huang H, et al. Malnutrition in patients with coronary artery disease: prevalence and mortality in a 46, 485 Chinese cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2022; 32 (5): 1186-1194. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.12.023 [8] Arero G, Arero A G, Mohammed S H, et al. Prognostic potential of the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in predicting all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease: a Meta-Analysis. Front Nutr, 2022; 9: 850641. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.850641 [9] DoiS, Iwata H, Wada H, et al. A novel and simply calculated nutritional index serves as a useful prognostic indicator in patients with coronary artery disease. International Journal of Cardiology, 2018; 262: 92-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.039 [10] Maruyama S, Ebisawa S, Miura T, et al. Impact of nutritional index on long-term outcomes of elderly patients with coronary artery disease: sub-analysis of the SHINANO 5 year registry. Heart Vessels, 2021; 36 (1): 7-13. doi: 10.1007/s00380-020-01659-0 [11] Kalyoncuoglu M, Katkat F, Biter H I, et al. Predicting one-year deaths and major adverse vascular events with the controlling nutritional status score in elderly patients with non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary Intervention. J Clin Med, 2021; 10 (11): 2247. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112247 [12] Raposeiras Roubin S, Abu Assi E, Cespon Fernandez M, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2020; 76 (7): 828-840. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.058 [13] Dentali F, Nigro O, Squizzato A, et al. Impact of neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio on major clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Journal of Cardiology, 2018; 266: 31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.116 [14] Wada H, Dohi T, Miyauchi K, et al. Pre-procedural neutrophil-tolymphocyte ratio and long-term cardiac outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis, 2017; 265: 35-40. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.08.007 [15] Ma Y C, Zuo L, Chen J H, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2006; 17 (10): 2937-2944. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040368 [16] Nahm F S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J Anesthesiol, 2022; 75(1): 25-36. doi: 10.4097/kja.21209 [17] Malekmohammad K, Bezsonov E E, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Role of lipid accumulation and inflammation in atherosclerosis: focus on molecular and cellular mechanisms. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021; 8: 707529. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.707529 [18] Xie Y, Feng X, Gao Y, Zhan X, et al. Association of albumin to nonhigh-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2024; 46(1): 2299601. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2023.2299601 [19] Roche M, Rondeau P, Singh N R, et al. The antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FEBS Lett, 2008; 582 (13): 1783-1787. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.057 [20] Lapenna D, Ciofani G, Ucchino S, et al. Serum albumin and biomolecular oxidative damage of human atherosclerotic plaques. Clin Biochem, 2010; 43 (18): 1458-1460. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.08.025 [21] Artigas A, Wernerman J, Arroyo V, et al. Role of albumin in diseases associated with severe systemic inflammation: Pathophysiologic and clinical evidence in sepsis and in decompensated cirrhosis. J Crit Care, 2016; 33: 62-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.12.019 [22] Lin X, Ke F, Chen M. Association of albumin levels with the risk of intracranial atherosclerosis. BMC Neurol, 2023; 23 (1): 198. doi: 10.1186/s12883-023-03234-2 [23] Liao L Z, Zhang S Z, Li W D, et al. Serum albumin and atrial fibrillation: insights from epidemiological and mendelian randomization studies. Eur J Epidemiol, 2020; 35 (2): 113-122. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00583-6 [24] Jin X, Xiong S, Ju S Y, et al. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, albumin, and mortality among chinese older adults: a population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2020; 105(8): 349. [25] Kalyoncuoglu M, Durmus G. Relationship between C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio and the extent of coronary artery disease in patients with non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis, 2020; 31(2): 130-136. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000768 [26] Kétlyn de Lima, Caryna Eurich Mazur, Mariana Abe Vicente Cavagnari, et al. Omega-3 supplementation effects on cardiovascular risk and inflammatory profile in chronic kidney disease patients in hemodialysis treatment: an intervention study. Clin Nutr ESPEN, 2023; 58: 144-151 doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.09.914 [27] Sproston N R, Ashworth J J. Role of C-Reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front Immunol, 2018; 9: 754. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00754 [28] Gao Y, Wang M, Wang R, et al. The predictive value of the hs-CRP/HDL-C ratio, an inflammation-lipid composite marker, for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and elderly people: evidence from a large national cohort study. Lipids Health Dis, 2024; 23(1): 66. doi: 10.1186/s12944-024-02055-7 [29] Eldrup N, Kragelund C, Steffensen R, et al. Prognosis by C-reactive protein and matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels in stable coronary heart disease during 15 years of follow-up. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2012; 22 (8): 677-683. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.11.003 [30] Li X, Liu X-H, Nie S P, et al. Prognostic value of baseline C-reactive protein levels in patients undergoing coronary revascularization. Chinese Med J-Peking, 2010; 123 (13): 1628-1632. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2010.13.003 [31] Liu S, Jiang H, Dhuromsingh M, et al. Evaluation of C-reactive protein as predictor of adverse prognosis in acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 18, 715 individuals. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2022; 9: 1013501. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1013501 [32] Bian C, Wu Y, Shi Y, et al. Predictive value of the relative lymphocyte count in coronary heart disease. Heart Vessels, 2010; 25 (6): 469-473. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0010-7 [33] Horne B D, Anderson J L, John J M, et al. Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? J Am Coll Cardiol, 2005; 45 (10): 1638-1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.054 [34] Waleria T Fonzar, Francisco A Fonseca, et al. Atherosclerosis severity in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: The role of T and B lymphocytes. Atheroscler Plus, 2022; 48: 27-36. doi: 10.1016/j.athplu.2022.03.002 [35] Wada H, Dohi T, Miyauchi K, et al. Prognostic impact of nutritional status assessed by the Controlling Nutritional Status score in patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Res Cardiol, 2017; 106 (11): 875-883. doi: 10.1007/s00392-017-1132-z [36] Olsen S J, Schirmer H, Bonaa K H, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary intervention: results from a nationwide survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs, 2018; 17 (3): 273-279. doi: 10.1177/1474515117737766 [37] Cruz Rodriguez J B, Alkhateeb H. Beta-Blockers, calcium channel clockers, and mortality in stable coronary artery disease. Curr Cardiol Rep, 2020; 22(3): 12. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-1262-1 [38] Luo L, Li M, Xi Y, et al. C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte index as a feasible nutrition-immunity-inflammation marker of the outcome of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly. Clin Nutr ESPEN, 2024; 63: 346-353. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2024.06.054 [39] Lessomo F Y N, Fan Q, Wang Z Q, et al. The relationship between leukocyte to albumin ratio and atrial fibrillation severity. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2023; 23(1): 67. doi: 10.1186/s12872-023-03097-y -

投稿系统

投稿系统

下载:

下载: